(1861 – 1928)

By Gwen McKinney

Ask half a dozen people about what reparations should yield, you’re likely to get six different answers: A check. A house. Free education. Student loan payoff. Healthcare for life. Or 40 acres – with or without the mule.

How do we accurately quantify the incalculable harm to the descendants of African slaves, then and now. Do we factor in the profits and privilege still reaped by textile and sugar barons, rolled into their accumulated dynasties and passed on to successive heirs over the centuries?

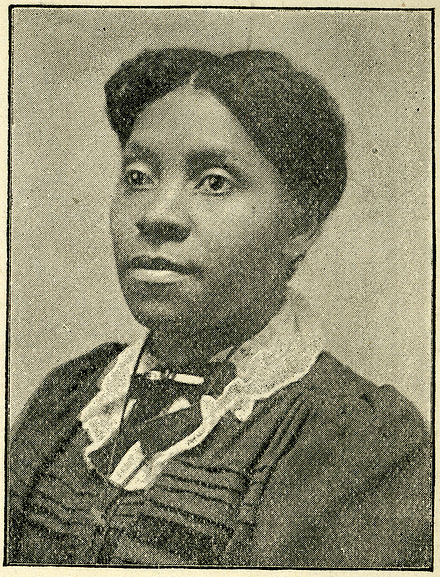

This story, less about rightful recompense, celebrates the bold but simple concept of a lowly washer woman who birthed it. Callie House, a Tennessee laundress born into slavery, dared to demand pensions for her fellow washer women. The circle would grow to include sharecroppers and other formerly enslaved people whose exploited labor was never compensated.

House, a self-educated woman, launched the late 19th Century campaign. She dared to believe her tribe, like Civil War veterans, was owed for the strained fingers and bent backs from servitude over wash tubs and in the fields ruled by slave owners.

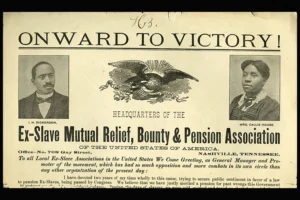

The humble request – for pensions to cover living and burial expenses – would blossom into a movement, and in 1897 House chartered the Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association (MRBPA). She joined with other relentless advocates, petitioning the government, filing lawsuits, organizing the ranks and galvanizing a following of more than 300,000 throughout the south.

The ruling powers – both in the north and south – took notice. They deemed Callie House’s advocacy an outrageous mockery to the American system. Holding to their premise: why would the U.S. government grant anything to former slaves.

In 1915, House’s organization filed a federal class-action lawsuit against the U.S. Treasury Department seeking $68 million, compensation calculated as the amount of a cotton tax collected between 1862 and 1868. The plaintiffs maintained the toil and unpaid labor of their ancestors produced the bounty and fueled the industrial revolution that made the U.S. the wealthiest country in the world.

The case was tossed out by the U.S. Supreme Court, and one year later, House was prosecuted for fraud under specious provisions of the U.S. Postal Service. She was sentenced by an all-White, male jury to a year in prison.

Who knew the courage and vision of Callie House would establish her throne as the Mother of Reparations. One of history’s hidden figures, her unstinting sacrifices and contributions endure as the unfinished business of a people’s quest for justice.

Today, the reparations movement enjoys widespread support. The late U.S. Representatives John Conyers (D-MI) and Sheila Jackson-Lee (D-TX) helped to enliven the conversation with a sustained legislative push in Congress.

In 2015, the National African American Reparations Commission was established. Composed of a multidisciplinary group of experts in law, medicine, policy, history and social justice advocacy, the Commission calls for “reparatory justice, compensation and restoration of African American communities that were plundered by the historical crimes of slavery… and American apartheid.”

Still pleading the cause ignited by Callie House, reparation advocates estimate every descendant of the formerly enslaved is due no less than $151 million for the atrocities committed over the centuries.

Gwen McKinney is the creator of Unerased | Black Women speak, an initiative devoted to developing narrative and storytelling for, by and about Black women.