By Gwen McKinney

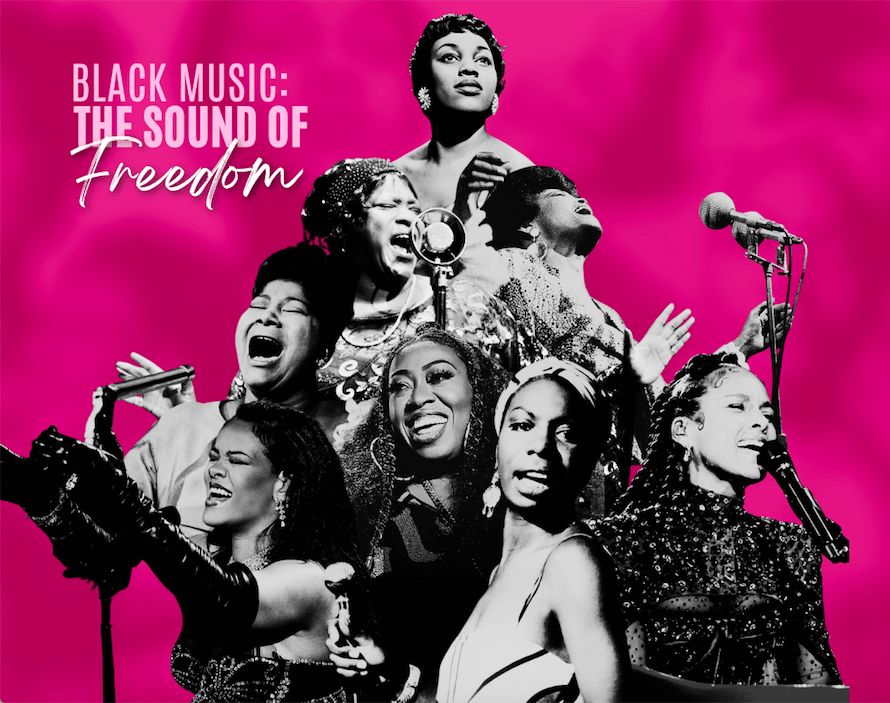

Black music is braided into the American origin story. The beats, rhythms and songs celebrate the Black experience that influenced every genre of this nation’s music from the 19th Century forward.

Deeply rooted in the Antebellum South, Black music was the first uniquely American sonic art form, transported from the ancestral homelands across the Transatlantic passage. Musicologists trace the roots of the American Blues sound to the “savanna hinterland” of West Africa including what is now Senegal, Gambia, Mali, Burkina Faso, Northern Ghana, Niger, and northern Nigeria.

“We have used music to advocate for our own collective freedom as people,” offers Ethnomusicologist Fredara Hadley. “Freedom is a refrain that reverberates throughout the lineage of Africa to the African diasporic to Black American music.”

Hadley references scholar Matthew Morrison whose new book Blacksound: Making Race and Popular Music in the United States uncovers the genesis of the popular music industry, emerging from slavery and blackface, usurping rhythms and sounds of enslaved people.

“In the early 19th century, white men primarily started extracting musical and cultural practices from Black people,” Hadley explains, “Refashioning them in caricature racist tropes. But it is that refashioning that has become America’s first popular genre.”

Leading up to the Civil War and into the early 20th Century, like its people, Black music survived. Faithful, jubilant and authentic, tempered by the quest for liberation and the sounds of freedom.

The music was a clarion call, from the plantations and cotton fields, to the jubilee tents, honkytonks and juke joints. Emancipation and the new century opened more opportunities for revues and show stages, with the evolution of minstrelsy to vaudeville.

The tempo of the drums. The banjo’s beckoning. The harmonica’s insistent pitch. The horn’s alluring call and response. It all flowed from the oral tradition of Africans in America. For the newly freed people, those sounds – sometimes bent or bold – were never broken. The musical forms echoed the Black lived experiences.

Whether coded signals for an escape from bondage; the spiritual salve of a rugged life; or the moaning heart of a lover done wrong, those notes derived from the early “Negro Spirituals.” Its evolution became an expression of hope and perseverance, relying on storytelling, resonating with pain and passion.

One of the most popular Negro Spirituals, said to be a favorite of abolitionist Harriet Tubman, is still sung today. Swing Low, Sweet Chariot reflects triumph and trauma. The words are a cloaked call to escape, an embrace of the here and now and an abiding faith in otherworldliness.

Swing low, sweet chariot,

Coming for to carry me home.

Swing low, sweet chariot,

Coming for to carry me home.

I look over Jordan, and what did I see,

Coming for to carry me home.

A band of angels coming for me,

Coming for to carry me home. Oh,

If you get there before I do,

Coming for to carry me home.

Tell all my friends I’m coming too,

Coming for to carry me home. Oh,

The brightest day that ever I saw

Coming for to carry me home.

When Jesus washed my sins away

Coming for to carry me home. Oh,

I’m sometimes up and sometimes down,

Coming for to carry me home.

But still my soul feel heavenly bound

Coming for to carry me home.

From the spirituals flowed melodies for the soul. It transitioned to a syncopation, improv of early folk music evolving into blues, jazz, gospel, swing, R&B, Hip-Hop and successive forms of popular rhythms that we enjoy today.

Gwen McKinney is the creator of Unerased | Black Women Speak, a public engagement initiative dedicated to amplifying voices and interests of Black women.