Black liberation in the United States has never been a closed-loop story. From the early 20th century to the present, Caribbean-born women have carried visions of justice across oceans, into newspapers, salons, courtrooms, and protests—where their voices helped reshape the very meaning of freedom. Their work made it clear: the fight for Black lives has always been global.

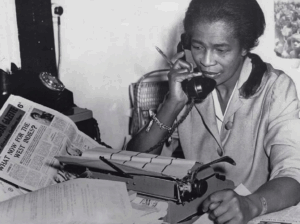

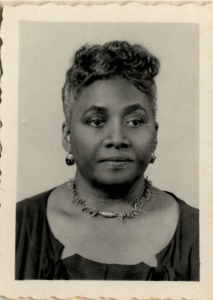

Claudia Jones was one of the sharpest minds in U.S. leftist politics. B

orn in Trinidad and raised in Harlem, she became a leader in the Communist Party USA and a fierce advocate for working class Black women, arguing that liberation required tackling racism, capitalism and sexism at once. Decades before intersectionality had a name, Jones pushed for childcare programs, affordable housing and equitable labor rights. Her activism drew the attention of federal authorities during the Red Scare, and she was eventually arrested and deported under the McCarran Act. From exile in London, she continued her work, founding the West Indian Gazette, Britain’s first major Black newspaper, and organizing early Caribbean indoor carnivals—cultural forerunners to today’s Notting Hill Carnival. Even from across the Atlantic, Jones remained a bridge between diaspora politics and American struggles for justice.

Though many of her contemporaries were men, Jones was far from alone. Amy Ashwood Garvey, co-founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), laid much of the ideological groundwork that her more famous husband, Marcus Garvey, would later popularize. A feminist and Pan-Africanist in her own right, Amy Ashwood helped organize global conferences on Black women’s rights and championed self-determination across the West Indies, Britain, and West Africa. Her influence extended through the UNIA’s reach and into a tradition of Black internationalist feminism that lives on today.

Jamaican poet and broadcaster Una Marson brought Caribbean cultural and political thought directly into British public life. As the first Black woman employed by the BBC, she used the airwaves to amplify anti-colonial voices and promote West Indian literature, while also confronting the intersections of racism and sexism she experienced in both Jamaica and England. Her work blurred the line between art and activism—another tool for global Black freedom.

In France, Paulette Nardal, a Martinican intellectual, writer, and translator, hosted a renowned salon in Paris that brought together Black artists, scholars, and revolutionaries from across the diaspora. These gatherings helped spark the Négritude movement, which championed Black consciousness and anti-colonial identity across the Francophone world. Nardal, though long overshadowed by her male counterparts, is now rightly recognized as a founding figure of modern Black international thought.

Throughout the 20th century, other Caribbean women continued to advance political change in ways both bold and behind the scenes. Figures like Shirley Chisholm, the Brooklyn-born daughter of Barbadian and Guyanese immigrants, became the first Black woman elected to the United States Congress in 1968. Her campaign slogan, “Unbought and Unbossed,” embodied the spirit of Caribbean political defiance. Chisholm’s presidential run in 1972 was groundbreaking—not just for its audacity, but for its clarity about the links between race, gender, class, and power.

Even in movements that became known through men’s names, Caribbean women were often shaping the agendas. Stokely Carmichael, born in Trinidad and raised in the Bronx, popularized the phrase “Black Power.” But it was women like Elma Francois, a labor organizer from Trinidad who helped radicalize public workers and lead strikes in the 1930s, who laid the groundwork for mass movements. Francois’s activism in Trinidad anticipated many of the civil rights tactics later used in the U.S., including worker mobilization, direct action, and radical political education.

What united these women across time and geography was a vision of liberation that transcended borders. They understood that Jim Crow laws, colonial rule, economic exploitation, and patriarchy were not isolated systems but interlinked mechanisms of control. They urged Black Americans and Caribbeans alike to think beyond national identity and toward a collective global struggle for dignity and justice.

Today, the contributions of Caribbean-born women—and their daughters—remain underrecognized in mainstream civil rights histories. But their fingerprints are everywhere: in the language we use to describe intersectionality, in movements for reproductive and labor rights, and in the continued effort to imagine Black freedom beyond borders. These women weren’t just participants in political movements—they were architects of liberation.

Joshua Levi Perrin is a writer and content curator for Unerased | Black Women Speak and communications and program manager at Funders Together for Housing Justice.