Bluford Residence Hall at the University of Missouri is named after Missouri journalist and publisher, Lucile H. Bluford. The dormitory, set on a campus she never graced because she was barred from integrating the all-White campus, is a physical testament to Bluford’s outsize influence.

Reporter. Activist. Editor. Publisher. Entrepreneur. Lucile Bluford didn’t just record history – she helped make it.

Bluford sued Missouri School of Journalism 11 times. She was initially admitted to the prestigious program but denied enrollment when school officials discovered she was Black. She fought the case up to the Missouri Supreme Court – and won to no avail when the university closed the program.

Bluford went on to carve out a stellar career as a civic activist and entrepreneur. SRPUnerased talked to DC-based communications executive and entrepreur, Sheila Brooks, Ph.D., who penned the biography, Lucile H. Bluford and the Kansas City Call: Activist Voice for Social Justice.

SRP: Why were you inspired to tell Lucile Bluford’s story?

SB: My biggest motivation came from my deep roots in Kansas City, Missouri. I grew up on the same street where sat the Kansas City Call, Bluford’s newspaper. I grew up during the height of the civil rights movement in the 1960s and always had an interest in African American entrepreneurs. Though I grew up among the working poor, most everyone in our community had a side hustle, a business. That’s why I always aspired to be a business owner after getting the training as a journalist, and also the training I got as a professor. When I went back to school for my doctorate, I decided the research I would do would definitely be focused on an African American woman entrepreneur. It was important to me that it be about a hidden figure. It was important to tell a story about women who had just as much significance as Ida B. Wells and Daisy Bates, but just never got the spotlight.

There were no biographies written about Lucile Bluford. This was really strange because they have a branch library dedicated to her. At the downtown Kansas City, Missouri library, all her papers are available. She is huge in the Midwest especially in Missouri and Kansas. Her story deserved to be told. Once she was turned away from the University of Missouri, they told her to go down the road, about 30 miles away, to Lincoln University, which had no journalism program.

It was because of her that Lincoln University instituted a journalism program. As a result, generations of Black journalists stand on her shoulders.

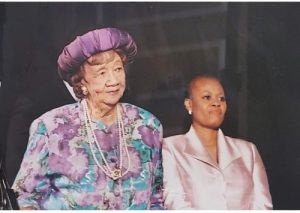

She graduated from University of Kansas in 1932, the only Black woman who graduated with a journalism degree. When she graduated, she went to work for the largest Black newspaper in town. Then journalists and activists, Roy Wilkins and Vernon Jarrett, were also working there. Her editor and publisher then encouraged her to go to graduate school. She was admitted to the University of Missouri Graduate Journalism School in Columbia, Missouri but then barred from attending when they found out she was Black. The case ended up in court for three years – 1939 to 1941. And after she prevailed, they shut down the school of journalism in 1941 so they wouldn’t have to admit her. Then 50 years later they awarded her with a Missouri Honor Medal for Distinguished Service and gave her an honorary Ph.D. There’s now a dorm named after her on the campus she could never set foot on. She was never deterred. She was active at 91-years old, 70 years as a journalist at The Call, until 2003 when she died.

I’m proud to say that the Kansas City Call is still in publication today – still sitting right there at that same corner, 18th and Vine. It’s an historic area.

SRP: Would you say much of her legacy has been untold or erased? And tell us about her legacy.

SB: I would not say it’s been erased. I would say it is little-known beyond Missouri and Kansas and the Midwest. Women in recent years have begun to claim our history. It’s time we gave Lucile Bluford her due.

There are some Black journalists, baby boomers, who knew and worked with her. My dissertation became the book. I just wanted to make sure the research was all there. Practically every journalist, activist and politician in that region, boomers and African American men and women knew her well because they were on the streets with her. I chose to capture a 15-year period from 1968-1983 because that was during a time of resistance and upheaval against injustice. I analyzed 358 of her stories (news pieces and commentaries), articulating her feminist standpoint, her take on issues of the day. I analyzed her contributions not just to civil rights but also to Black feminist causes. She positioned herself not just as a journalist but as a publisher and an owner, influential in legislation and policy.

This is a woman who writes about the 1968 riots and the Missouri National Guard came to town because they refused to close schools on the day of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s funeral. She called out the then police chief and said he was ultimately responsible for the riots in the city and he was eventually fired.

She often talked about systemic race and sex discrimination and shone a light on how women were kept out of jobs usually held by white men. She was an advocate for those stories of women’s rights and school desegregation. Many of those stories she wrote using the pseudonym Louis Blue. Those stories were about eradicating injustices, stories about women

prisoners and the penal system, stories about the criminal justice system. There were stories she covered when she feared for her life. No one knew she was writing these stories, people thought they were written by a man. She was an amazing woman. The stories were stories of protest when she wrote as Louis Blue. The city’s black population in the 1960s was about 62 percent. There was a very strong vibrant Black community.

I think it was around early 1977 that she wrote about the police chief again and his dismissal. Bluford had called for another police chief to be fired. This was not just about unrest; there was a series of 10 unsolved murders, all young Black women. This was why she called for the firing of the police chief.

Bluford was also a very active member of NAACP, and she persuaded the NAACP to call for his resignation. After that he really resisted. But eventually they ousted him. That case speaks to what is going on now as communities call for defunding police across the country.

For more than a century, Black newspapers have contributed significantly to Black civil rights and racial justice, for women’s rights. They were known for publishing strong views on Black protests and women’s suffrage. And because Bluford was publisher and editor, she used her social position to propel these issues forward. She made a difference.

She used her journalistic voice to break down the barriers against injustice during a time when mainstream news ignored our stories. Social media has become that forum. Everyone has a camera on their phones, everyone can videotape. And the first forum for news is on social media. The Call has been publishing for 100 years and still publishes every Friday.

SRP: Who are our contemporary Lucile Blufords and why?

SB: I can think of people who are doing her work today like Nikole Hannah-Jones of the New York Times whose Pulitzer Prize-winning work launched the 1619 Project and Soraya McDonald, cultural editor at Undefeated. I respect and admire those women so much for bringing that voice to life. And there are so many others.

We have to tell these untold stories about women who advocated for our rights that we just don’t know about. What’s going to be the history for our children? What are we passing on to them?

We have to celebrate women who argued for economic independence. The right to work, earn wages, pay equity, and to provide for our families. They laid the groundwork that helped make progress in this new century. So, many African American women have become lawyers and writers and business owners and presidents of universities. That whole movement gave them a voice in the organizations who supported them. The significance of voice is so important to consider. It’s about society, our role in society. How valuable it is to have lived experiences. These women could speak about their lived experience; voices matter in race and politics. It’s a reflective voice for us to hear. It helps for others to hear your voice and experience.

The Black press has played a significant role in giving voice to the Black community. That’s why it’s so sad to see those Black newspapers disappearing. There was no way our mothers would let a week go by without reading that Kansas City Call and once we were old enough, saw that we read it too. That’s where we went for our source for news, knowledge and understanding the contributions of racial and gender equality. One of the things that surfaced in my research was the importance of black feminism. Bluford spoke from a black woman’s viewpoint through her lived experience.

SRP: What are the Bluford lessons and/or unfinished business that you want to address today?

SB: The unfinished business from my standpoint is a documentary about Lucile Bluford, given the wealth of research I surfaced. There’s only so much you can put in a book. The publisher wanted to keep it concise and advised against making the book too long. The book was about Bluford and the stories she covered. The book was about one thing. And there were so many other stories of people who knew her that could be told. I didn’t really get to talk about real people who knew her, who are still living and could share vibrant oral histories about her contributions in Kansas City, Missouri. I interviewed about a dozen people in May 2019 that knew Lucile Bluford including, one woman who was 90-years-old and another who was 99-years-old, two of her best friends. I interviewed Rep. Emmanuel Cleaver (D) – Missouri, who said he would not have become mayor of Kansas City much less a Member of U.S. Congress if it were not for Ms. Bluford. Period. Drop the mic.

It’s tough when you run a business and you are serving clients. But still, you want to do a project of your own. I’m getting the video treatment ready and about to start pitching the documentary. That’s my unfinished business. It’s so important that Lucile Bluford’s story be told in multiple media forms.

Related Content

BLACK WOMEN’S ROUNDTABLE CORONAVIRUS DOROTHY HEIGHT MELANIE CAMPBELL MELANIE CAMPBELL BOLD AND UNBOSSED NATIONAL COALITION ON BLACK CIVIC PARTICIPATION NATIONAL COUNCIL OF NEGRO WOMEN