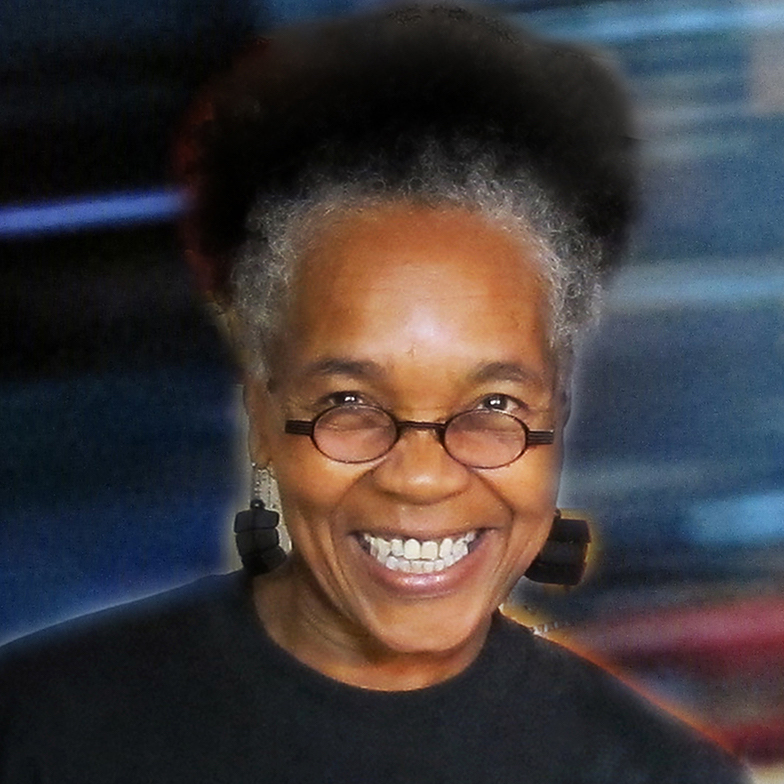

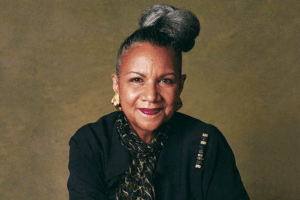

Sharon Farmer grew up planning to hone her musical training into orchestral performance. But somewhere between high school bassoon practice and Ohio State University activism, she stumbled on photography.

Sharon Farmer grew up planning to hone her musical training into orchestral performance. But somewhere between high school bassoon practice and Ohio State University activism, she stumbled on photography.

“The camera is my path to everything I care about – protests, history, the arts, politics, people making change,” says Farmer, who’s been at the job in far-flung capacities since 1974.

She acknowledges that the eye of her camera rarely closes.

Homespun and folksy, Sharon Farmer refuses to just shoot. Her subjects beckon. She meets them; gets in front of them and then engages. Approaching the craft with humility and reverence, it’s never about her.

“You have to get out of the way. If you’re all in it, the images will be riddled with flawed judgment.”

Her path began with the Black student college newspaper, Our Choking Times. The activist and student government vice president took on photography, mesmerized by the science of the craft.

“I was fascinated how images would appear on blank paper after being dipped in chemicals. It was fascinating alchemy for me,” she remarked. First working at the Columbus Call & Post, that set her on the path to photojournalism on and off campus.

From there she earned a “minority internship” with AP that she remembers relegated her to shooting statues – a problem that she would resolve by “going around” her immediate supervisor. Photography would become her career path, leading to commercial gigs shooting babies and portraits, to photojournalism with the Washington Informer, the Afro-American, the Washington Post and other mainstream news organizations including the Associated Press DC bureau where she served as assignment/photo editor. Her work has also graced the walls of the the Smithsonian Museum.

One of her passion projects was in 1978 when she collaborated with Bernice Johnson Reagon and Sweet Honey in the Rock, creating the cover photography for the vinyl album B’lieve I’ll Run On…See What The End’s Gonna Be.

That collaboration and all Farmer’s pursuits are weaved by the common thread of humanity. “It’s always about people. People let you know what they think. It’s turmoil, struggle, achievement. It’s what people care about, their opinions and what makes them move.”

Opening a wider lens for her magic eyes, the native Washingtonian landed at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, becoming the first woman and Black person to direct the White House Department of Photography.

During the administration of President Bill Clinton, she would oversee five photographers and a staff of some 35 technicians and support staff. She’d travel around the nation and the world, always focused on capturing people.

Like all things in Sharon Farmer’s path, the White House position was not a job she was looking for. It found her and she followed.

“The camera shows lunacy and beauty,” explains Farmer. “Photography is like a brain…it heads you to where you need to go. You don’t have to think about it. You just have to get there. And then you’ll see what you need to capture.”

Farmer rejects bragging rights in opening doors and breaking barriers. “I have no pride in being the first of anything. It says we haven’t come as far as we need to go. To be the first or the only says we have a lot of work to do.”