Photo: Kent Nishimura/Bloomberg via Getty Images

By Liz Courquet-Lesaulnier reprinted from Word in Black

Emaciated, stricken with stage 4 pancreatic cancer, Rep. John Lewis, civil rights icon, needed to see it for himself. Steadied by a cane, wearing a purple and black mask to guard against the COVID-19 pandemic raging across the nation, the congressman from Georgia walked through Black Lives Matter Plaza in downtown Washington, D.C.

Lewis posed for pictures with Mayor Muriel Bowser, who commissioned the mural as an act of defiance. With arms folded, the two leaders stood on 16th St. NW, the words BLACK LIVES MATTER stretched on the pavement behind them. The bright yellow letters, two city blocks long, large enough to read from space, gleamed like a yellow brick road to the White House — then occupied by President Donald Trump.

Lewis’s June 7, 2020, visit came just days after protests over the murder of George Floyd rocked the nation. The mural, painted on June 5, 2020, was a defiant response to the police killing of Floyd — and a reminder to the city that the Trump administration ordered law enforcement to attack local protesters in that block. Lewis died 40 days after his visit.

On Monday, nearly five years later, on Bowser’s orders, city workers began dismantling the mural. The plaza became another victim of the ongoing whitelash against the election of President Barack Obama, the Black Lives Matter movement, and indeed, the very existence of Black folks in these United States.

“First, they attacked critical race theory. Then, they banned books. Then DEI, Now they’re erasing Black Lives Matter Plaza,” the Black Lives Matter Global Network Foundation posted on X on Monday.

“Big mistake. You can’t erase truth,” the organization wrote. “Republicans hate that they have to walk past it. Hate that it reminds them of our power.”

But at a time when the scourge of police killing Black people hasn’t stopped, when law enforcement budgets are on the rise — and when Trump, returned to power five years later, pardoned two D.C. cops imprisoned for killing a Black man, then trying to cover it up — it’s an open question whether the mural had any power at all.

“We Can’t Afford to Be Distracted”

When she and Lewis visited the plaza in 2020, Bowser posted the photos of herself and the congressman at the plaza with an inspiring message: “We’ve walked this path before, and will continue marching on, hand in hand, elevating our voices, until justice and peace prevail.”

Not long after Trump returned to power in January, however, Republicans — emboldened by control of the White House and both houses of Congress — took aim at the mural and put Bowser in a squeeze. Rep. Andrew Clyde, a Georgia Republican, introduced legislation that was more like an ultimatum: get rid of Black Lives Matter Plaza or lose millions in federal funding.

Mayor Muriel Bowser and Rep. John Lewis at Black Lives Matter Plaza on June 7, 2020. Photo courtesy of Mayor Muriel Bowser/X

Mayor Muriel Bowser and Rep. John Lewis at Black Lives Matter Plaza on June 7, 2020. Photo courtesy of Mayor Muriel Bowser/X

Clyde could make that demand due to what’s known as “home rule,” a quirk in D.C. government. Washington, D.C. isn’t a state, but it’s allowed to govern itself — up to a point. Because it’s considered a federal jurisdiction, Congress gets the last word on city issues if it chooses to and must approve D.C.’s budget every year.

Without statehood, Washington can be subject to the whims of lawmakers, who sometimes use their power as a cudgel to punish the city if it does things they don’t like.

And Bowser got Clyde’s message, loud and clear.

The mural helped the city through a difficult period, “but now we can’t afford to be distracted by meaningless congressional interference,” Bowser wrote on X. “The devastating impacts of the federal job cuts must be our number one concern.”

Intimidation or Practicality?

Artist Keyonna Jones, a D.C. resident who worked on the mural, understood Bowser’s choice.

“We either fight for this, or we lose funding,” Jones told WTOP. “People have lost their homes, people have lost their jobs, and we need to keep whatever we can” to preserve the city.

Still, it was a 180 for Bowser. In a 2020 essay for The Washington Post, she vowed Trump — who wanted Gen. Mark Milley, then-chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, to have troops shoot unarmed protesters — would not intimidate the city.

The president “became the latest to trample our rights as U.S. citizens,” she wrote. “He is not the first and, unfortunately, he will likely not be the last. But by standing together, we pushed back more forcefully than we ever have before.”

“Performative” Justice

Not everyone was convinced by Bowser’s bravado.

Calling the Black Lives Matter mural “performative,” the D.C. chapter of Black Lives Matter accused Bowser of political grandstanding. They pointed out that her administration failed to address systemic issues that led to protests in the first place, like police violence and housing inequality.

A splashy mural “is supposed to reflect the value of Black lives,” Brandi Thompson Summers, a University of California-Berkeley professor and former D.C. resident, told NPR in August 2020. “But you don’t actually have to make the city habitable for Black people.”

Indeed, when John Lewis — a survivor of the 1965 Bloody Sunday civil rights protest in Selma, Alabama — visited the mural, activists had already expanded its message to include DEFUND THE POLICE. The words remained on the pavement until August 2020, when Verizon workers paved it over as part of a construction project.

The next year, as Republicans slammed her over the “defund the police” message, Bowser increased the D.C. police budget. Critics pointed to the move as evidence that the mayor’s commitment to racial justice was merely symbolic.

Cop Cities

Just two years after Floyd’s death, an ABC News analysis of 109 city and county police budgets found 8 in 10 of them spent more on law enforcement than they did in 2019. In 2024, researchers from Oxford University found “no evidence that BLM protests led to police defunding.” In fact, “in cities with large Republican vote shares, protest is associated with significant increases in police budgets,” they wrote.

According to data analysis by Mapping Police Violence, in 2024, 1,252 Americans were killed by police — more than in any other year in the past decade.

Screenshot via Mapping Police Violence

Screenshot via Mapping Police Violence

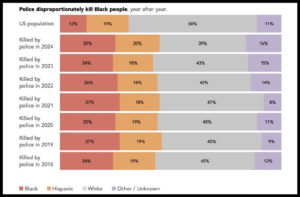

Despite being 12% of the population, Black people were 25% of those killed by police in 2024. In 2020, the year of Floyd’s murder, Black people were also 25% of those killed by police. In fact, Black people are disproportionately killed by cops every year.

Screenshot via Mapping Police Violence

Screenshot via Mapping Police Violence

But if public symbols like Black Lives Matter Plaza didn’t stop police from killing Black people — if the words were only performative — why has there been such a visceral backlash to it, and why have Republicans demanded that Bowser remove it?

Symbols Matter

In the months after the murder of George Floyd, 168 Confederate statues, monuments, streets, and buildings were removed or renamed. Outraged, Trump told Fox News, “We should learn from the history. And if you don’t understand your history, you will go back to it again.”

By that logic, then, because Black Lives Matter Plaza was part of history, it should have stayed put.

“D.C. is erasing history by removing Black Lives Matter Plaza—once a powerful symbol of justice—amid pressure,” civil rights attorney Benjamin Crump wrote on Threads.

But Clyde, the Republican from Georgia, gloated about it on X: “One week after I introduced legislation to rename Black Lives Matter Plaza, workers have started dismantling it. Making D.C. Great Again!”

Right-wing commentator Charlie Kirk, sporting a wide smile, filmed the start of the plaza’s removal, calling it the “end of this mass race hysteria happening in our country.”

Not so fast, wrote Los Angeles-based screenwriter John Destes. “Charlie Kirk thinks a little paint thinner means black lives don’t matter anymore,” he tweeted.

Black Lives Have Always Mattered

Ten days after he died, the hearse carrying Lewis’s remains stopped at Black Lives Matter Plaza on its procession to the U.S. Capitol Building for his memorial service. In a posthumous essay published on July 30 in The New York Times, Lewis wrote that seeing young people protest Floyd’s murder “inspired me.”

Millions of people, he said, had put aside the poison of division and embraced justice and unity.

“That is why I had to visit Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington, though I was admitted to the hospital the following day,” Lewis wrote. “I just had to see and feel it for myself that, after many years of silent witness, the truth is still marching on.”

The removal of the mural, however, is not the end of the story.

Symbols are powerful, but real change — an end to Black people dying at the hands of police; an end to Black mothers dying more often than whites during childbirth; an end to Black folks dying earlier, being more likely to live in poverty, more likely to attend an underfunded school, more likely to serve time in prison — is a matter of life and death.

Lewis knew, long before the mural existed, that Black America has always mattered. Our ancestors who bled for justice knew our lives mattered. Always. And no amount of ripping up streets can change that.