We capture the history making role of a woman who loved entertainment but could only soar by becoming a French expat. The story, written for Unerased by Julia Browne—archivist, storyteller, and tour guide of Black Paris.

Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, March 19, 1890 – December 13, 1960

Paris Pathfinders and Expats

Where could Black women gather one hundred years ago to confidently craft new and intersectional identities, imparting freedom of expression and wings to soar? Paris, bien sûr (of course)!

So says a descendant of Africa who was born in Britain, raised in Canada by West Indian parents and a longstanding part time resident of France. Julia Browne enlivens a perspective wearing two hats: historian and tour guide. Through her Black Heritage in France Walking The Spirit tours, she brings to life the drive and challenges that Black women shouldered in their determination to exist, renew and revive in that transnational sphere known as the “City of Lights.” In this three-part tribute Julia Browne profiles Paris Pathfinders and Patriots – an artist, an intellectual and an entertainer. Their common thread is woven from talents revered in Paris while spurned in their country of birth.

So says a descendant of Africa who was born in Britain, raised in Canada by West Indian parents and a longstanding part time resident of France. Julia Browne enlivens a perspective wearing two hats: historian and tour guide. Through her Black Heritage in France Walking The Spirit tours, she brings to life the drive and challenges that Black women shouldered in their determination to exist, renew and revive in that transnational sphere known as the “City of Lights.” In this three-part tribute Julia Browne profiles Paris Pathfinders and Patriots – an artist, an intellectual and an entertainer. Their common thread is woven from talents revered in Paris while spurned in their country of birth.

“Beauty was conceived in paradise but found in the depth of hell.”

That refrain, etched in the journal of Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, speaks to the pain and pathos that she endured. She found the pathway to Paris as the only escape from a life destined for domestic labor in her native Providence, RI.

Prophet, the first African American graduate of the prestigious Rhode Island School of Design, faced bleak prospects, even in that liberal Northern city. Swimming against the tide, this talented young sculptor had heard of the promise of Paris. Scrimping, saving and armed with $380 hard-earned dollars, she landed there in August 1922.

At the age of 32, this artist turned expat was determined to conquer elusive aspirations. But without a study abroad grant or financial sponsorship, her existence turned out to be the most difficult of all the African American artists who preceded or followed her to France.

Even in the face of destitution, Prophet gained freedom to create in an environment that did not stigmatize based on race nor gender. Armed with a relentless work ethic learned from her parents, Prophet put creating art before everything else, quite often to the detriment of her mental and physical health.

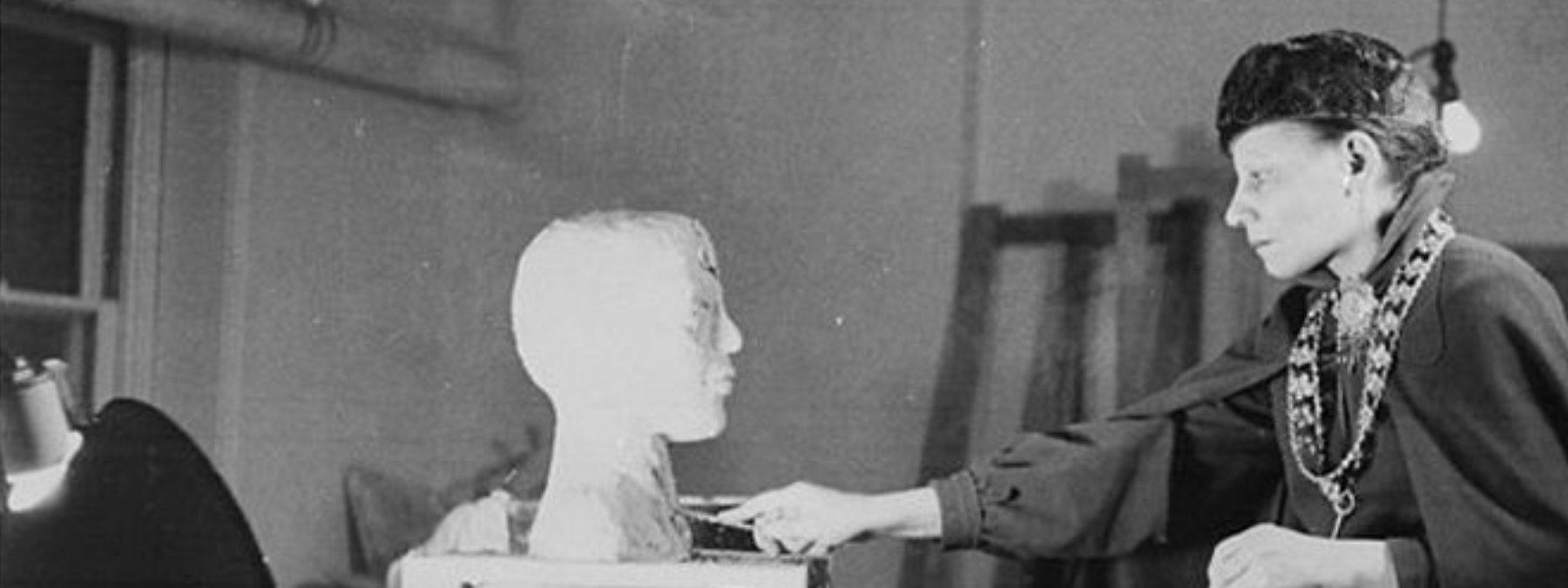

Living in a string of damp, poorly lit, unheated studios, she tackled her first piece with calm assurance and the savage thrill of revenge, certain she was creating a living thing. Before the bust was completed, her money had evaporated.

Through her 12 years in Paris, the constant in her existence was hunger, starved for food and paying work.

Her diary tells of resorting to theft – an uneaten potato and meat from a dog’s bowl at the home of an acquaintance. The scrambling was perpetual, relying on the generosity of friends, strangers, landlords.

“This thing money, or lack of it, is too crushing. It keeps me from working when I should be expressing that which I learned from each day lived,” wrote Prophet in her journal. “Sculpture is an expensive medium… but I have not chosen my medium of expression; it has chosen me.”

Single-minded about mastering her craft, Prophet took classes at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, the state-run Faculty of Art, as well as with private teachers. She found models who would pose for free, be it a man met in a cafe or an unattractive woman. Her masterful pieces ‘Silence’ and ‘Poverty’ embodied her grinding reality.

But Prophet’s masterpieces metamorphosed after seeing African sculpture for the first time at France’s triumphant Colonial Exhibition in 1931. It signaled the birth of exquisite works born of pride in her roots. Descendant of both African and Native American heritage, she wrote to her mentor WEB Dubois that people were seeing for the first time “aristocratic heads of thought and reflection.”

It inspired one of her most celebrated pieces, Congolaise, a head of a Masai warrior.

Prestigious art exhibits in France were already accepting her work and her talent was showcased beside innovative international and French artists. This discovery was unfolding at a time when U.S. galleries refused to show any work by Black artists.

By the early 1930s, Prophet had arrived, armed with the credentials of studying with Parisian masters, exhibited in Parisian art shows, and a body of work to prove European skill. Her work finally received acclaim and was purchased by respected art houses in New York, Boston and Newport.

Her piece Discontent now resides in the Museum of Rhode Island School of Design. Congolaise graces the permanent collection of the Whitney Museum.

Prophet returned permanently to the U.S. in 1934. A year later she co-founded the first visual arts department at Spelman College where young black women could gauge the price of continuing in the face of despair.

Teaching gave her the opportunity to give what she had never received – the encouragement to tell Black women in their formative years that they too could soar.