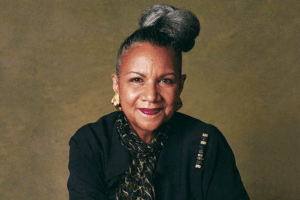

Denise Rolark-Barnes acknowledges that print journalism was her first love but confesses to quietly stoking another passion that was less toil than the excruciating rigor of running a weekly community newspaper.

In 1994 Rolark-Barnes swapped passions for legacy. With the passing of her father, Dr. Calvin W. Rolark, Sr., founder of the Washington Informer, she joined an august group of warrior women, chroniclers of their people’s story.

The Black Press has recorded the journey through abolition, emancipation, lynching, migration, civil rights, and social pathways that stitch a community into whole cloth. Black women publishers – unlike their fathers and spouses – historically are driven by intersectional activism, less than business motivation. Their ranks include suffragist leaders like Mary Ann Shadd Cary and Ida B. Wells who wielded their presses as a weapon for democratic change.

“It seemed to be my path,” reflects Rolark. “Running the newspaper just felt like the thing to do. I could showcase what Black people were doing to make this place called America better for us to live.”

Better got bad and then grew worse.

By the late 20th Century, integration – the crusade that the Black press had always championed – ironically hastened the erosion of their readership. Aging audiences, shrinking advertising and explosion of online news and content rendered print products almost obsolete. This relentless demise engulfed daily newspapers and all print publications across the country.

“Keeping the operation going often feels like I’m pushing from the back of an 18-wheeler with a driver who’s pressing his foot on the breaks,” remarks Rolark.

Fast forward to the 2020 Pandemic. The crisis has plunged the industry, especially smaller business operations, on to life support. But when the mainstream media sneeze, the Black Press gets pneumonia. Stay-at-home quarantines have dramatically impacted print editions of most Black weeklies, which enjoy boosted circulation from the “pass along” tradition in hair salons, churches and other meeting places that have shuttered over the past several months.

Rolark, former president of the umbrella trade group the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA), has long grappled with challenges of viability. Like NNPA colleagues nationwide, she’s confronted with a single option: Digitize or Die.

That returns us to Rolark’s not-so-secret passion.

“I’ve always been fascinated with the storytelling power of radio,” says Rolark who occasionally hosted her father’s radio show Sound-Off. “For typical users, newspapers require work. TV is often imposing. But radio is comfortable, enticing you to use your ear and imagination.”

From reading to listening, digital audio podcasts – a medium that attracts cross-generational appeal – won Rolark’s favor and a seed grant from Facebook to launch a training and production studio.

How do you innovate to what’s new and relevant with little resources? Over the years, Rolark witnessed what seemed like massive transitions, from typesetting to desktop publishing; from black and white to color pages; from paper to online sites; from the ground to the digital cloud.

Forced to step up her game with reimagined resources, Rolark is transforming the 800-square foot bottom level of the Informer building into the podcast studio. Two grown sons, and a virtual rolodex of supporters and stakeholders will help transform a bold idea into a new institution. Launch date is by the summer.

The Informer Podcast Studio envisions serving as a model for peers, creating an income-generating, news-production and “train the trainers” institute. High school and college interns will support productions and partner with community and advocacy organizations. The space will be available for commercial utilization as well.

Located in Anacostia, the last bastion of predominantly Black and low-income DC, the Informer aims to continue its 55-year mission, giving a voice to those largely ignored or erased from the power conversations.

Rolark says digitize or die means realizing the reach and value of the Internet and beyond; forming new alliances, greater shared resources, and partnerships with entities unconsidered in the past.

Black newspapers traditionally serviced people starved for information, for work, for politics, to know what was happening in the neighborhood and the world. “They are still starved,” offers Rolark, “but their appetite requires a different substance.”