By Amaya Smith, originally published on theGrio.com

As we mark Black Women’s Equal Pay Day, we see that despite Black women’s long history in the workforce, they continue to be underpaid due to systemic racism and sexism.

If you’re into Black Twitter or Black TikTok then it’s safe to say that you’ve seen the recent conversations around Black women and the economics of heteronormative dating and marriage. Whether that be the Sprinkle Sprinkle philosophy or the uproar over Eboni K. Williams’ dating choices or the recent news around Keke Palmer, the internet is on fire about Black women and what our partners should or should not be required to bring to the table.

What’s missing from this conversation are the real economic numbers behind these dating decisions.

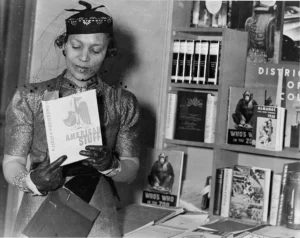

So here are the facts: Black women have one of the highest “labor force participation rates” for women. Meaning Black women are more likely to be in the workforce compared to white women and Latinas regardless of age, marital status or children in the home.

This isn’t a new phenomenon. According to economist Nina Banks, historically even when most women were homemakers, “In 1880, 35.4 percent of married black women and 73.3 percent of single black women were in the labor force compared with only 7.3 percent of married white women and 23.8 percent of single white women.”

And it doesn’t stop there. As we mark Black Women’s Equal Pay Day — an un-holiday that acknowledges that Black women working full time make 67 cents for every dollar white men earn — we see that despite our long history in the workforce Black women continue to be underpaid due to systemic racism and sexism.

Any conversation around Black women’s demands for equality in dating partners must also examine who the breadwinners in America’s families are — and these statistics follow the same trend.

Black mothers are more likely to be the sole or primary breadwinners — bringing home the majority of the household income or equally sharing in that responsibility — compared to Latinas and white women, with 68.3% of Black mothers fulfilling this role in comparison to 41% of Latina mothers and 36.8% of white mothers.

This means that while other women are able to rely on a partner or other family members when they have children, get ill or need to leave the workforce for other reasons — not so much for Black women.

What many are witnessing in social media chats is the compounded frustration of many generations of Black women who have more than pulled their weight to lift up not just the Black family, but the overall American economy.

In short, Black women are tired of being “strong Black women.”

Black women being underpaid and undervalued isn’t just a Black women’s thing. It has a widespread impact on the 3 million households that Black moms who are breadwinners support, the over 10 million jobs they fill in the economy and the spending power of nearly $1.5 trillion they bring with them.

But the way to remedy this is not to activate your Twitter fingers to criticize Black women’s dating choices or to get into drawn-out circular conversations about who is accountable for economic and cultural challenges in the Black community, but rather to be an ally for Black women and their economic futures.

You can start by supporting equal pay for equal work. This includes calling on companies to openly share their salaries so that we can end pay discrimination. Asking companies to post salaries on their job descriptions also helps ensure that Black women aren’t taking jobs only to later find out they were offered less than their white counterparts.

You can advocate for a national policy to give workers more paid time off, which would allow Black women the ability to rest and recuperate and take time off if they have children, adopt a child, get sick or need to take care of a sick loved one.

You can support affordable child care that ensures that Black women who have children and need or want to work have daycare that doesn’t bankrupt them — and Black women who are daycare providers are not struggling on wages that barely support their own families while they take care of others.

You can support unions, which give Black women access to higher wages, better benefits and the ability to speak out against racism and intimidation on the job without the fear of being harassed or fired.

You can also call for more infrastructure jobs to go to Black women as we implement the Biden-Harris administration’s recent historic investments to increase good jobs in STEM, construction and domestic research.

Sure these actions aren’t as satisfying as dropping comments in the Shade Room about Gabrielle Union and Dwyane Wade’s financial arrangements, but they are important policy changes that we can all support to ensure that Black women — a group that has long given so much to this country and its economy — are finally given some appreciation and support where it really counts — in their pocketbooks.

Amaya Smith is a small business owner and vice president for marketing and communications at the National Partnership for Women & Families, a nonprofit that advocates for economic, gender, racial and health justice.