Marsha P. Johnson (left) and Sylvia Rivera (right) were considered pivotal Mothers of the queer rights movement.

Marsha P. Johnson (left) and Sylvia Rivera (right) were considered pivotal Mothers of the queer rights movement.

By Levi Perrin

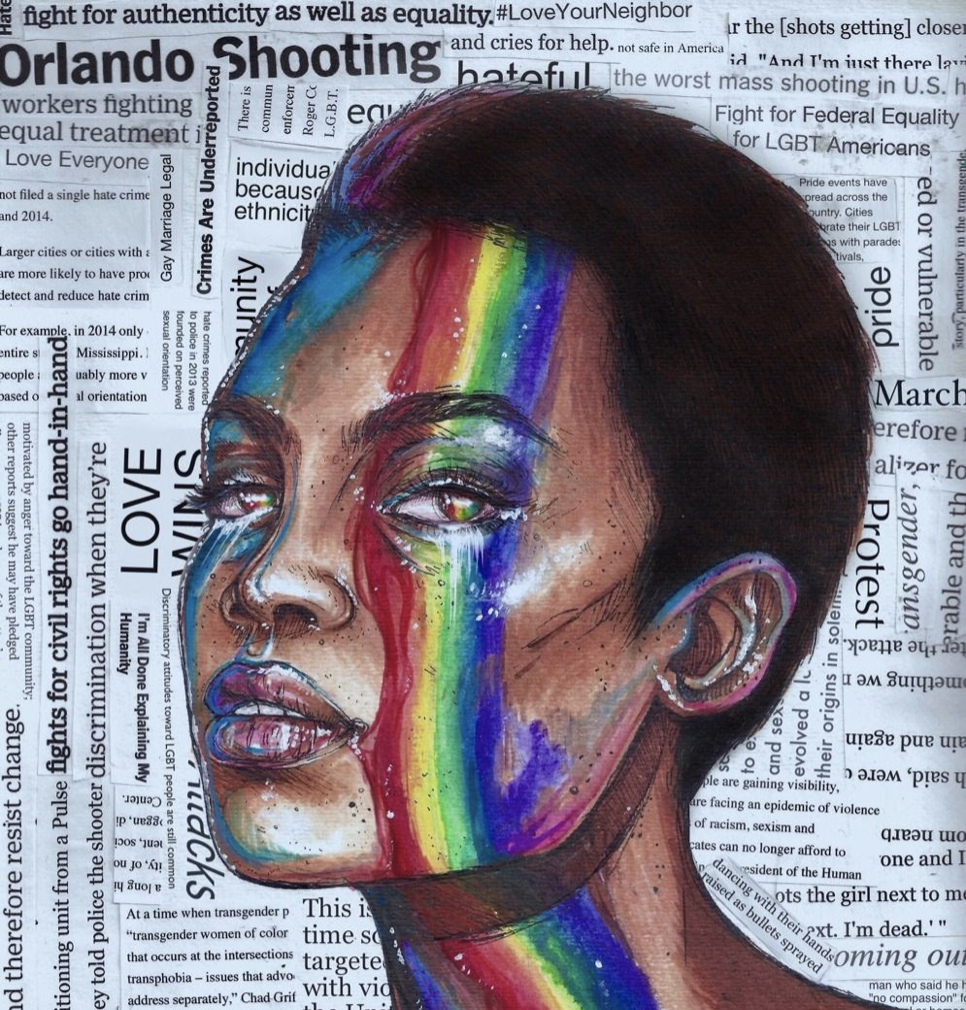

Pushed to the edge, with no armor except their fury and spirit, transwomen – Black, Brown and all shades between – should have been centerstage. They put their bodies on the line and launched a movement that we know today as Pride. Withstanding the whips of police brutality on that sticky summer night outside the Stonewall Inn, Black transwomen built the foundation for the house of queer self-determination, brick by brick. As a cisgender queer man, I proclaim it is past time to welcome them inside.

Fifty-two years later, Black transwomen continue to be erased, literally and figuratively, from the very movement they boldly launched. The road from Christopher Street in Greenwich Village is paved with backlash to exclude transwomen from mainstream LGBTQ movements. The exclusion was just one of many failed attempts to gain allies from the white professional class. Pride, as they believed, was not a multiracial resistance coalition demanding equity, inclusion, and opportunity. Instead it was a branding opportunity for corporate America to repackage, resell, and “reward” only those whose existence was not too far out of the cultural mainstream.

Then and now, Black and Brown transwomen are still pushed to the margins as if transness can be isolated from queer freedom.

Bré Rivera, the Program Fellow of the Black Trans Fund, succinctly weaves the connection on how gender bridges, rather than divides, the movement.

“A lot of folks think that trans justice only affects trans and gender nonconforming folks. But trans justice is gender justice,” she reflected during an SRP interview. “The work that trans folks are doing to achieve justice in this world, not only impacts us – it impacts cisgender people. It impacts folks who don’t have to spend time thinking about their gender identity and how they navigate the world.”

According to the National LGBTQ Task Force, Black transwomen are far more likely to experience serious roadblocks and harms. They have a 26% unemployment rate, 41% have experienced homelessness, 34% have household incomes under $10,000 and nearly half have attempted suicide.

Queer movement allies have attempted to address these concerns by creating safe spaces and amplifying the voices of BIPOC transwomen on social media, but safety without intentionality, resources, and a racial lens on inequality is often fleeting.

Wanton violence against trans people, mostly Black women, continues to rise. The death rate in May 2021 of 27 victims is already over half the total deaths in 2020, though this number is likely an undercount due to under reporting and erasure of trans people. Last year was reportedly the most violent year on record for trans people since 2013.

Hope Giselle, actor, author and creator of the Allow Me Movement, speaks to the violence.

“The thing we have to be cognizant of as Black people – the only time we are safe is when we dictate that we get to be safe. Outside of that, everything is a gamble, and this is something that LGBTQ people want allies to understand, that we shouldn’t always have to be the ones to create safe spaces.”

Resistance against erasure is what drove trans pioneers Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera to fight back at Stonewall. It is what led them to create and find safety in the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries – an organization that addressed the material needs of femmes, transwomen and others sidelined by gay leaders to appease conservatives.

They set off radical resistance against the status quo that created a shared movement that is carried from one generation to the next – a movement to continue ringing the bell signaling the hope of freedom.

For a deeper dive visit these sources:

Marsha P. Johnson, Queen of the Village.

Marsha P. Johnson, Queen of the Village.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eZj5n8ScTkI

Yoruba Richen, What The Gays Rights Movement Learned From The Civil Rights Movement, TED.