By Tracy Chiles McGhee

This article is part of Unerased | Black Women Speak’s December exploration Claiming Our Space: Preserving Our Future.

In the heart of Harlem, where Black culture, resilience, and brilliance have thrived for generations, one organization is fighting to ensure that this legacy is never forgotten. While We Are Still Here (WWSH) is on a mission to preserve Harlem’s rich history and tell its stories authentically. Through groundbreaking initiatives like the SIGNS OF THE TIMES®: Harlem Markers Project, WWSH places historical markers throughout the neighborhood, honoring the figures and moments that have shaped not only Harlem but the broader African Diaspora.

“These markers are vital,” Karen D. Taylor, the Founder/Executive Director of WWSH, asserts. “If Black people do not claim our story and control the narrative, we will wind up with the half-truths, lies, omissions, and the generalized strident disrespect that Black people have suffered for far too long.”

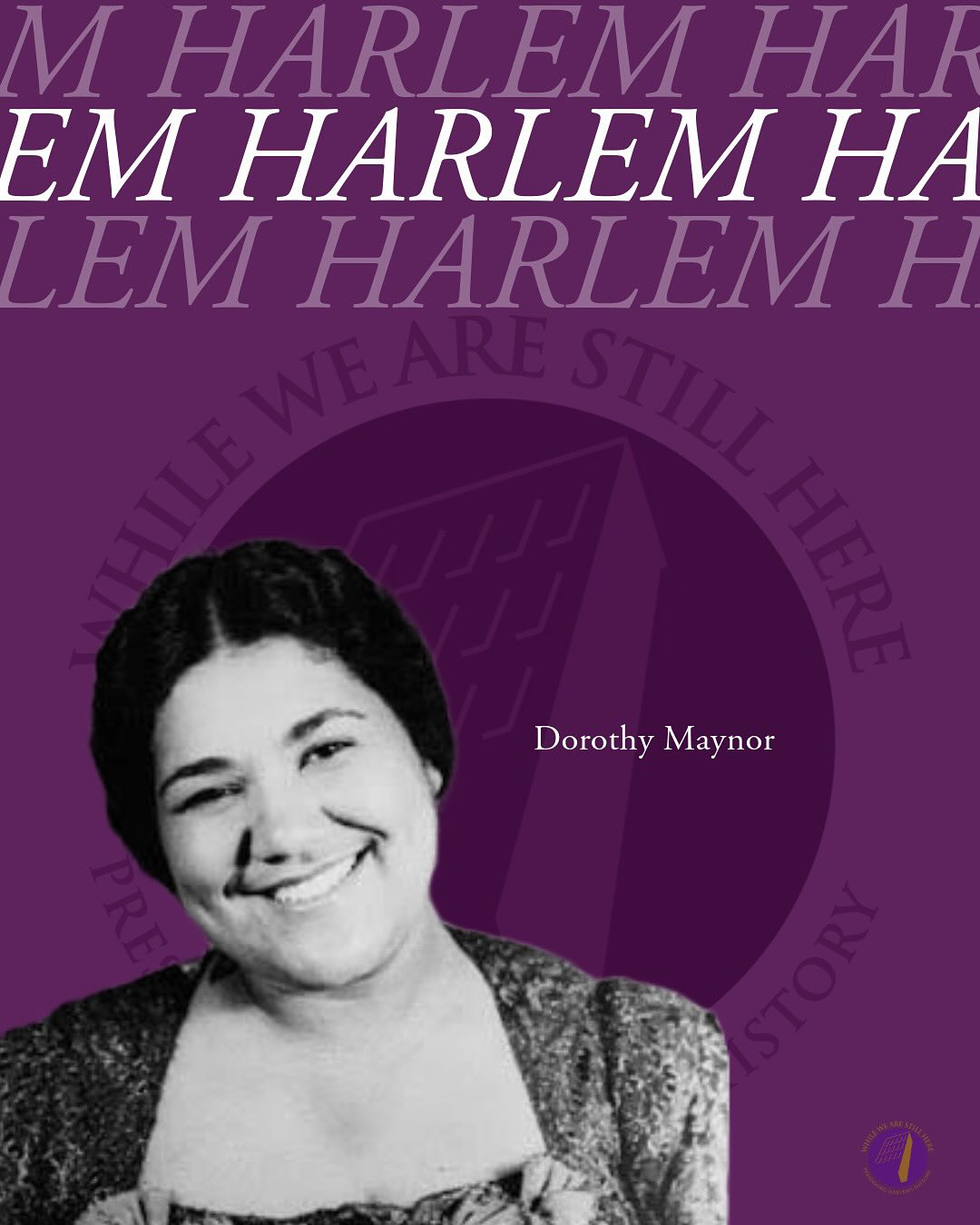

Dorothy Manor

One example Taylor shares is the marker for Dorothy Maynor, a concert soprano and founder of the Harlem School of the Arts. Despite Maynor’s monumental contributions, the building was renamed Herb Alpert Center after significant donations from the Herb Alpert Foundation. “While we appreciate his generosity, erasing Dorothy Maynor’s name is glaring disrespect of her legacy. Wealth should not eclipse the contributions of those who built these institutions.”

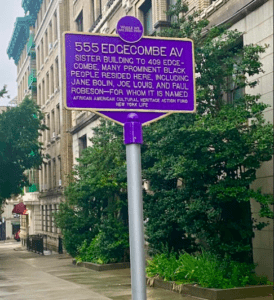

WWSH also honors historic residences like 409 and 555 Edgecombe Avenue, home to notable figures such as sociologist and civil rights leader W.E.B. Du Bois, singer and actress Lena Horne, the first African-American female physician in Harlem Dr. May Edward Chinn. That space was also occupied by boxing champion and activist Joe Louis, jazz legend and bandleader Count Basie, and the first Black woman judge in America Jane Bolin, and many more.

Gentrification: The Cost of Racial Displacement

Historical residence 555 Edgecombe Avenue

Gentrification in Harlem isn’t merely about rising rents—it’s about systemic racial discrimination. Says Taylor,“The new tenants in my building are all white. Are there no qualified Black applicants? Of course there are. But real estate workers devalue Black communities while prioritizing white renters and buyers,”

Taylor recalls the stark disparities in Harlem’s past: neglected grocery stores with subpar produce, streets left unswept. Now, with an influx of white residents, suddenly there are fresh food markets, new garbage cans on every corner, and an increased police presence. The message is clear: resources follow whiteness.

Taylor believes language matters. “I don’t like the word ‘gentrification.’ It’s too sanitized. This is racial displacement—a deliberate push to erase Black presence and replace it with a sanitized version of what developers deem profitable.”

The experience of actors like Wendell Pierce, rejected for a Harlem apartment due to systemic bias, underscores this reality. As Taylor notes, “If a celebrated actor like Pierce faces this, imagine the hurdles for everyday Black folks.”

Art and Advocacy: Mobilizing Community

Art plays a pivotal role in Taylor’s advocacy. “Art is a way into people’s consciousness,” she says. Through writing, curation, and performance, Taylor engages the community, inspiring residents to reclaim Harlem’s story. WWSH also plans to develop curricula tied to its historical markers, ensuring younger generations connect with and protect Harlem’s heritage.

Taylor’s advocacy extends beyond history. She critiques the broader social systems fueling displacement. From landlords raising rents to exploit demand, to white residents expressing hostility toward their Black neighbors, gentrification alters the very soul of Harlem. “Some white women in my building won’t even ride the elevator with their Black neighbors,” she laments.

Steps Toward Claiming Space

To counteract these forces, Taylor urges action:

- Tell Our Stories: “Initiatives like markers, books, and films are essential. If we don’t control our narratives, others will distort them.”

- Organize and Advocate: Taylor calls on Harlem residents to mobilize. “We must challenge discriminatory practices in real estate and demand accountability.”

- Invest in Community: “Support Black-owned businesses, attend local events, and preserve spaces that celebrate Black culture.”

- Educate and Empower: By involving younger generations, instilling pride and responsibility in Harlem’s legacy.

Looking Ahead

Through relentless advocacy and creative initiatives, Taylor ensures Harlem’s past is not forgotten and its future remains vibrant. “We must be organized and committed to engaging in these processes. Otherwise, in years to come Harlem as a Black cultural phenomenon will be suppressed, erased, sullied, and/or appropriated.

In a time when Black communities are under constant threat of erasure, Karen D. Taylor reminds us of the power of resistance and the necessity of storytelling. Harlem’s history – unapologetically and affirmatively – is Black history.

Tracy Chiles McGhee is a Writer and Constituency Engagement Advisor for Unerased | Black Women Speak.